Results Summary:

- Residents who consume water from private (domestic) wells are more likely to experience higher nitrate levels in their drinking water.

- Testing drinking water from domestic wells is essential to gain a realistic understanding of nitrate contamination.

The average concentration of domestic well nitrate levels in Nebraska is above 7 mg/L – but, below the 10mg/L safety standard. Although the average hides the nuances of nitrate concentrations in domestic well water, it underscores the need to focus on domestic wells in the larger nitrate management effort. As such, this article attempts to understand the temporal trends in nitrate levels observed in domestic wells in Nebraska.

Trends are used to understand the movement of a subject, which in this case is the concentration of nitrate in domestic wells over time. A more detailed description and more information on trends and a technical synopsis are available in a previous publication by the DWFI - “Nitrate management in Nebraska community water systems is a complex issue,” which is the precursor to this article.

The drinking water outlook for Nebraska

In Nebraska, community water systems provide more than 80% of drinking water needs. These water systems are required to comply with federal water quality standards and the wells used by community water systems as source-water are largely protected by voluntary community efforts such as Wellhead protection areas (WPAs). Among other contaminants, nitrate is a regulated compound that must measure less than 10 mg/L for community water systems to be allowed to maintain operations. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) set this standard in 1992 and enforces its regulation. This nitrate threshold is called a maximum contaminant level (MCL) and was first imposed to prevent methemoglobinemia (also known as blue baby syndrome)1. Today, there is evidence that nitrate concentrations are correlated with adverse health outcomes23. However, causality is not established.

Not all Nebraskans have access to quality-controlled drinking water. A large part of the concern about nitrate contamination in drinking water is not just that nitrate levels are increasing in some areas. It is also because some of the 400,000 residents of Nebraska who depend on domestic wells for drinking water are likely unaware of how much nitrate they might be exposed to via their drinking water. Unlike community water systems, domestic wells do not require contaminant testing or treatment of domestic wells.

Average nitrate trends do not represent problem areas

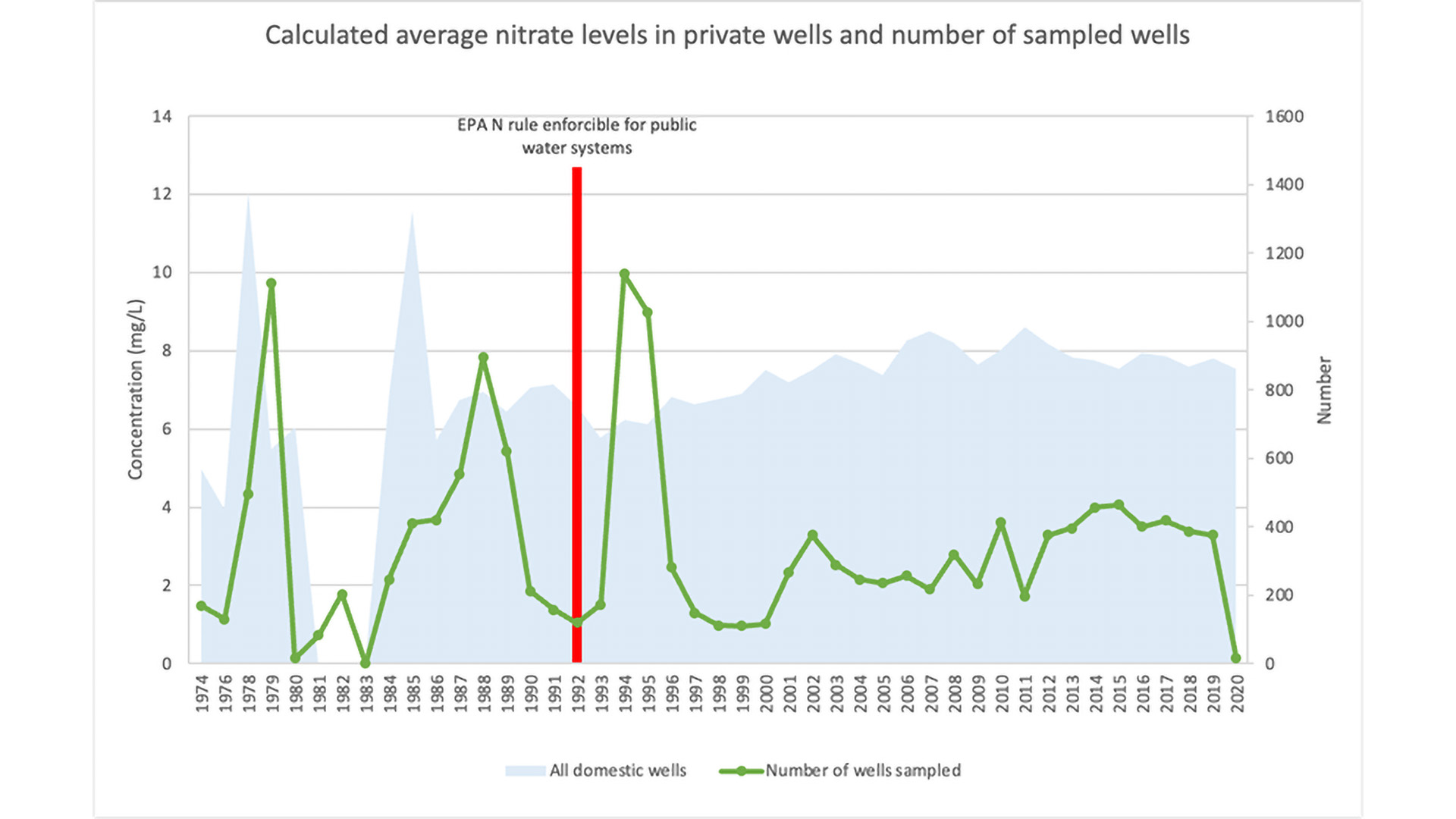

The currently available data on nitrate levels in domestic wells may be misleading when aggregated, because annual averages smooth the highs and lows of the data series, and data collection is not consistent over time. The average levels of nitrate measured in the last 45 years show that nitrate levels in Nebraska have not changed extraordinarily (see Figure 1); they remain above 7 mg/L and below the MCL established by the EPA. The number of wells sampled for nitrate increased after 1992, which may be attributed to the Nebraska well registration requirements imposed in 19934 or the EPA nitrate concentration rule. Even though the EPA regulation is only enforceable with community water systems, it is possible that the enforcement action triggered interest from local water managers to cross-reference the nitrate levels of public water systems with the observations of domestic well nitrate levels. Data collection has remained consistent in recent years, hovering around 400 wells per year. However, these measurements are likely to be over-represented in areas that have known nitrate leaching issues. This suggests that our knowledge of the extent of nitrate levels in domestic wells is limited and insufficient to make decisions on all domestic well drinking water users in Nebraska.

Figure 1: Average nitrate levels calculated in domestic wells and number of wells sampled. Data Source: Nebraska Groundwater Quality Clearinghouse.

The effectiveness of protections against nitrate leaching

Public wells have some protections from excess nitrate leaching due to designating WPAs around the wells. WPAs are voluntary community designations that prevent water contamination in public water supply wells that are used to provide water to communities. As such, the WPA designation is not related to domestic wells. WPAs are often located around populated areas in the state. Domestic wells located in or around WPAs are likely to benefit from these community efforts to protect drinking water compared to domestic wells located outside of WPAs, which are not protected against groundwater contamination in any systematic way.

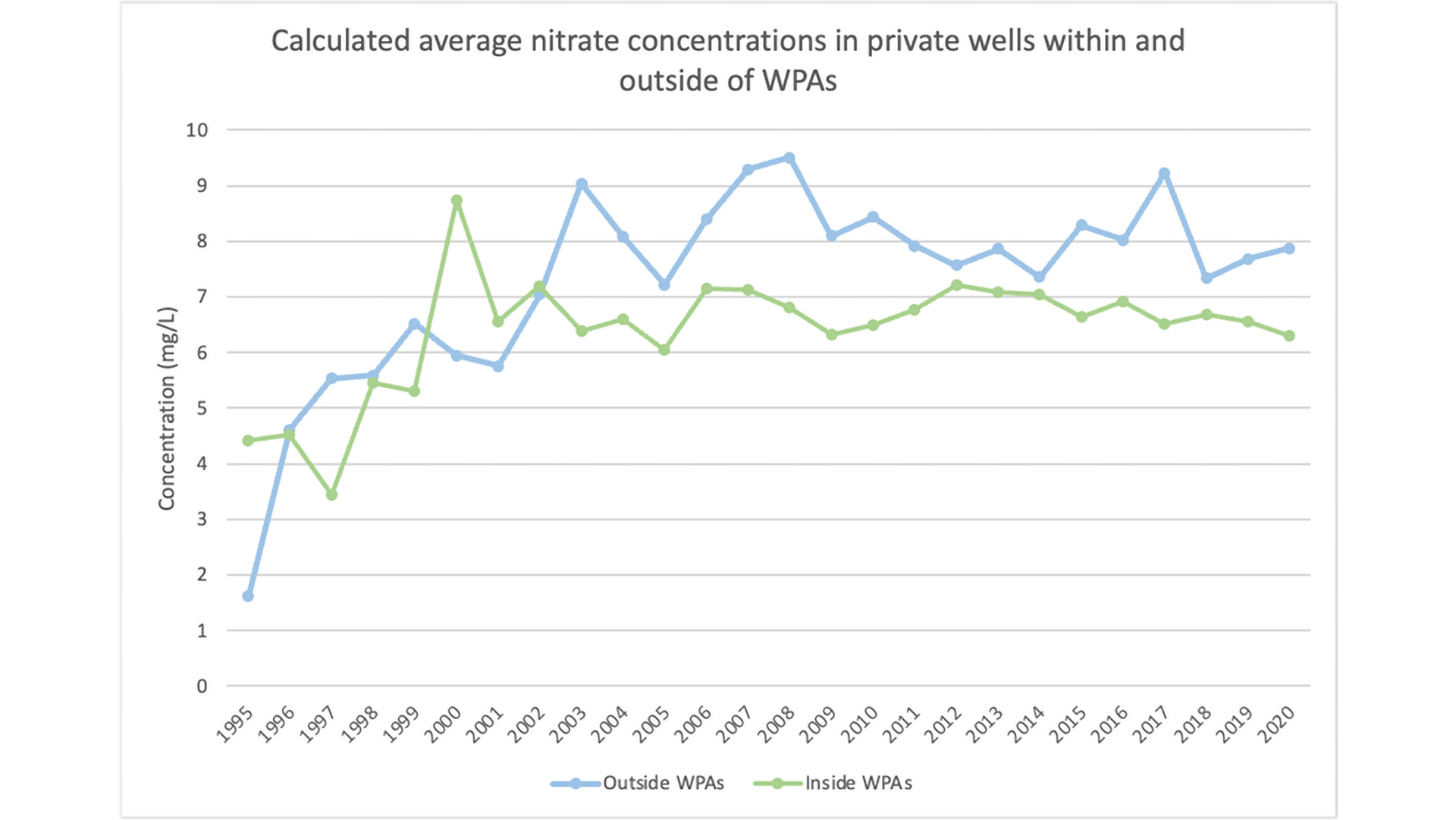

To further demonstrate how WPAs affect nitrate levels in domestic wells, nitrate samples between 1995 and 2020 were identified separately as within or outside of WPAs (Figure 2). Wells that are within WPAs have consistently remained below the nitrate concentration levels observed in wells outside of WPAs. It is especially encouraging to note that this divergence occurred within a few years of the Nebraska Legislature passing the Wellhead Protection Area Act in 19985.

Figure 2: Calculated average nitrate concentrations in domestic wells within and outside of WPAs. Notes: Data are limited to wells with above median (median=13 years of nitrate samples data) nitrate observations between 1995 and 2022. Data Source: Nebraska Groundwater Quality Clearinghouse.

Data availability and quality variability present challenges in conducting statistical analyses

Unlike public water systems, domestic well owners are not required to test their well water. This results in ad hoc data availability and makes analyses, such as temporal trends, less accurate. Although this article reflects assumptions to make the nitrate analysis more representative, it is difficult to further delineate the data in a meaningful way to demonstrate case-based examples. One of the main reasons for this dilemma is the inconsistency in nitrate testing and the reporting of findings. The Nebraska Rural Poll (RRP) of 2022 indicated that fewer than one-third of the respondents had tested their well water for nitrate. Among those who did test, high-income households (over $100,000) were twice as likely as lower income households (less than $40,000) to have tested their well water6. This suggests that in addition to a possible awareness gap, there might also be a cost burden for some individuals and households.

Another reason for the inconsistency in nitrate observations in domestic wells is non-randomness of the data. Data randomness is essential for accurate statistical analyses because disproportionately large amounts of data from wells with high (or low) nitrate concentrations can artificially inflate (or deflate) average nitrate calculations. Such calculations could lead to conclusions that may not represent the true state of domestic well water nitrate levels. These discrepancies could be a realistic concern in Nebraska for the following reasons: (1) households tend to test their water only if they suspect a possible nitrate contaminant problem or (2) because the local Natural Resources District (NRD) or public health department may have identified and tested domestic wells suspected of being part of a nitrate hotspot. Data collected through such deliberate measures are likely to overstate the magnitude of nitrate trends in domestic wells. The statistical results reported in this publication have accounted for these biases to minimize their impact on the results.

Limitations of water purification as a solution to high nitrate concentrations in well water

NRDs and public health departments recommend that domestic well owners periodically test their water for nitrate and other chemicals. More consistent and frequent testing can inform water managers about the extent and trends in water quality concerns that can help them develop solutions in the future. Test results also inform residents of the need to act if nitrate levels exceed the EPA-regulated minimum.

Reducing nitrate contamination in domestic wells is a long-term management effort that will likely take several years to achieve tangible benefits. Therefore, it is important for people in households with high concentrations of nitrate in domestic wells to take immediate action to protect themselves from excessive consumption of nitrate. Two commonly available equipment options for domestic well owners to mitigate contamination are point-of-use reverse osmosis (RO) or ion exchange (IX) systems.

Although water purification systems ensure short- to medium-term drinking water safety, they are not an ideal or sustainable long-term solution due to added costs and complications. In addition to the cost of the purification unit and installation, these systems need twice as much water input as they provide in water output and require regular maintenance to ensure their efficiency. This translates into additional electricity usage and possible water insecurity in areas where groundwater supplies fluctuate. Along with harmful chemicals and nutrients, RO and IX systems also remove other nutrients/minerals in water that are essential for human health. While public water systems add minerals back to the water supply after purification, domestic well owners must find alternative means of supplementing the minerals lost in the RO and IX process.

There are many reasons households do not test their domestic well water, including privacy concerns, cost, lack of awareness, etc. Therefore, subsidized or free testing kits7 , subsidies for water purification units8 and widespread awareness campaigns on nitrate-related drinking water quality concerns9 will likely increase domestic well testing and improve water quality.

Acknowledgements

The Water, Climate and Health Program and the College of Public Health project at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Health and Economic Impact Analysis of Nitrate Contamination of Groundwater in Nebraska, and the Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute at the University of Nebraska provided support for this research project.

The author appreciates the input and guidance received during many conversations with personnel from the Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy, Hastings Utilities, The Bazile Groundwater Management Area Project, as well as researchers from the University of Nebraska System, especially Crystal Powers (Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute at the University of Nebraska, Nebraska Water Center, and Nebraska Extension), Katie Pekarek (Nebraska Extension) and Renata Rimšaitė (Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute at the University of Nebraska). Appreciations to the Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy for providing access to the Nebraska Groundwater Quality Clearinghouse data that made this assessment possible. The views expressed in this report are those of the author.

1For more information see https://www.epa.gov/dwreginfo/chemical-contaminant-rules#:~:text=There%20is%20an%20acute%20health,levels%20of%20nitrate%20or%20nitrite.

2For more information see Ward, M. H., Jones, R. R., Brender, J. D., De Kok, T. M., Weyer, P. J., Nolan, B. T., … & Van Breda, S. G. (2018). Drinking water nitrate and human health: an updated review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(7), 1557.

3For more information see Sherris, A. R., Baiocchi, M., Fendorf, S., Luby, S. P., Yang, W., & Shaw, G. M. (2021). Nitrate in drinking water during pregnancy and spontaneous preterm birth: a retrospective within-mother analysis in California. Environmental health perspectives, 129(5), 057001.

4For more information see https://dnr.nebraska.gov/surface-water/update-responsibility-owners-water-rights-and-water-wells

5For more information see http://dee.ne.gov/NDEQProg.nsf/OnWeb/WHPA

6For more information see https://ruralpoll.unl.edu/pdf/22naturalresources.pdf

7For more information see https://hpj.com/2023/11/30/free-nitrate-sample-kits-for-private-drinking-water-wells-in-nebraska/#:~:text=Nebraska's%20private%20drinking%20water%20well,%2DPrice%2DList.aspx.

8For more information see http://dee.ne.gov/Publica.nsf/pages/22-051#:~:text=Rebates%20for%20100%25%20of%20the,also%20include%20costs%20for%20testing.

9For more information see https://knowyourwell.unl.edu/