By: Jude Cobbing1, Cody Knutson2, Renata Rimšaitė1

1 Senior Program Managers, Daugherty Water for Food Global Institute at the University of Nebraska

2 Planning Coordinator, National Drought Mitigation Center, University of Nebraska

INTRODUCTION

Agricultural water policy and water law relating to Tribal Nations in the United States have a unique history and differ in important ways from policy and law outside of Reservations. This publication provides an overview of Tribal water rights and agricultural water use on Tribal Reservations. Tribes’ rights to adequate water have long been recognized in federal law. However, quantifying the amount of water a Tribe is entitled to can support new opportunities for water resources development and increase sovereignty over land and resources (see below). Fewer than one in 10 of the more than 700 Reservation areas have quantified water rights.

WATER USE FOR AGRICULTURE

- There are 587 Tribes federally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, located on more than 700 Reservation areas1.

- Almost 720,000 irrigated acres are located on Reservations, but not all this irrigated land is managed by Tribal members. Reservations are often a checkerboard of Tribal and non-Tribal lands.

- Many Tribes rely on water for both commercial agriculture and subsistence farming. About 10,000 farms on Reservations are smaller than 10 acres and about 4,500 farms on Reservations exceed 500 acres.

- Tribal water management in agriculture is usually shaped by cultural values and traditional knowledge systems. For many Tribes, water—together with fire, air and earth—is one of the basic elements of life. It is often an inseparable component of Tribal spirituality, which strongly influences how Tribes manage agricultural activities and address their challenges.

- Tribal water use for agriculture faces a variety of challenges. In addition to weather-related concerns, agricultural water use can be constrained by fragmented land tenure; a lack of irrigation infrastructure; financial limitations; and difficulties in attracting private investment due to concerns over sovereign immunity.

- Tribal responses to water-related agricultural challenges are often based on Tribes’ traditional ecological knowledge, developed through intergenerational narratives and community-focused stewardship. These insights inform sustainable agricultural practices and influence water policy-related solutions, such as incentive-based water management tools (e.g., water transfers, dry-year leasing and water banking) and the adoption of efficient irrigation technology systems (e.g., center pivots).

- Agricultural water use on Tribal lands is inherently tied to water rights and the resource management and policy priorities of each Tribe.

LEGAL CONTEXT OF WATER RIGHTS ON TRIBAL LANDS

- The Winters Doctrine is a foundational legal principle in U.S. federal Tribal law that establishes that federal Reservations have rights to sufficient water even if those rights are not explicitly stated in treaties or statutes. The doctrine dates from a 1908 U.S. Supreme Court case, Winters v. United States.

- Tribal water rights under the Winters Doctrine are typically senior to most state-based water rights. Tribal water rights cannot be taken away if unused (unlike many state-law rights that follow the Prior Appropriation doctrine2). The U.S., as a trustee, holds these rights on behalf of Tribes, affirming their legal status and protection.

- Holding senior water rights does not necessarily mean that a Tribe can access or use all their entitled water. Quantifying the rights can be an important step in Tribes taking full ownership of their water.

- Quantifying the exact amount of water a Tribe is entitled to is often resolved through negotiated settlement rather than litigation. This process can take many years. Until rights are quantified it is difficult for Tribes to make full use of them.

- A settlement will generally include federal funding to develop critical infrastructure to access and utilize the Tribe’s quantified water rights. Funding and quantification can allow a Tribe not only to use more water for agriculture, but also to trade water, use it as collateral or engage in other activities that can benefit the Tribe.

- One criticism of water rights settlements is that some settlement funding has been slow to materialize and waives future water claims, placing a restriction on Tribal sovereignty. On the other hand, if properly negotiated, settlements can bring essential funding and legal certainty to provide the basis for enhanced tribal sovereignty.

- The lack of a water rights settlement does not infringe on Tribes’ legal right of access to water for basic needs, but it might make such basic access more difficult.

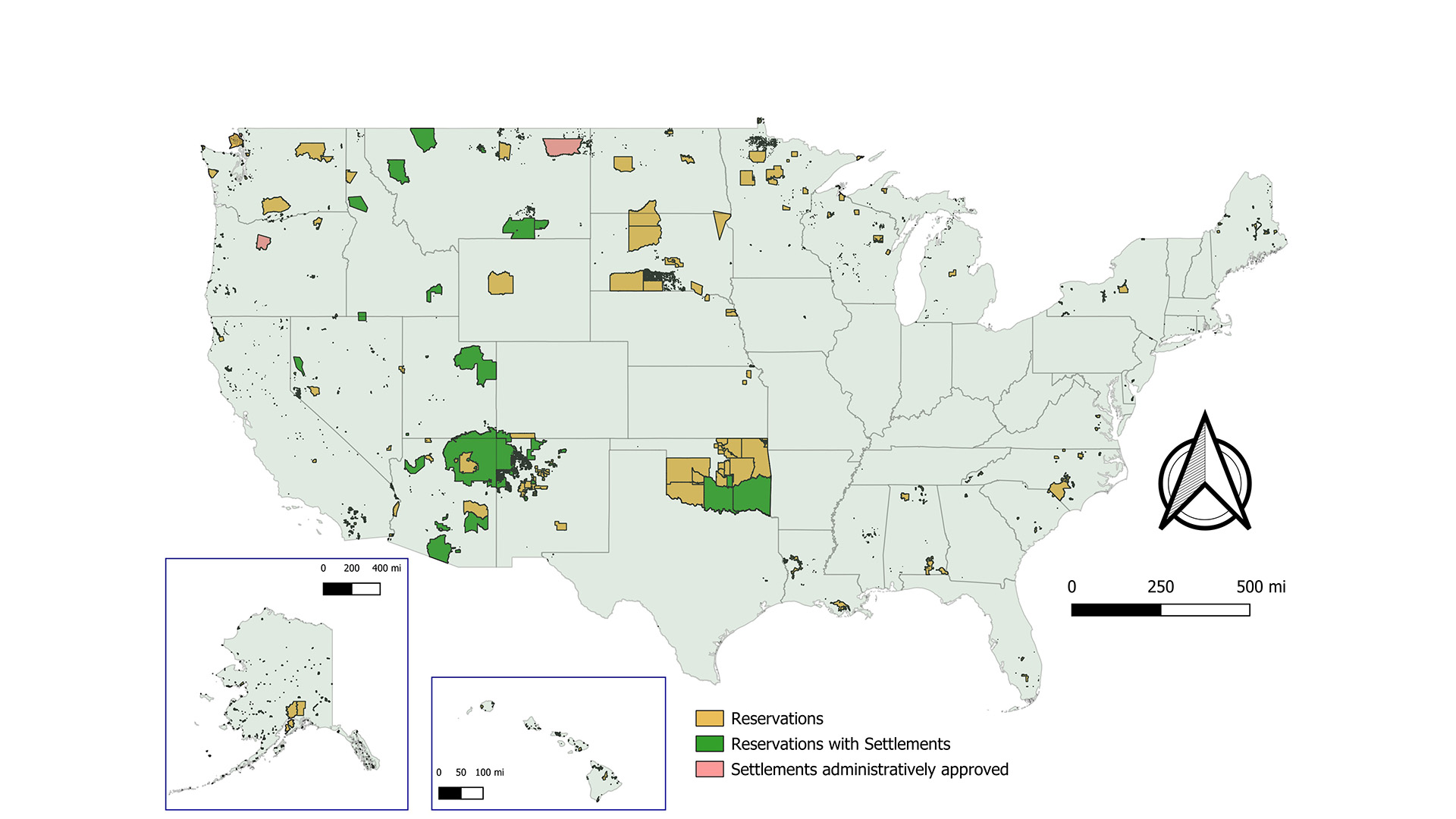

- 35 Tribes (out of 587 federally recognized Tribes) have water rights settlements and another 4 have administratively approved but not yet enacted water rights settlements. In other cases, agreements between or amongst Tribes and other water users exist but are not yet administratively approved.

- Tribal reservations with water rights settlements are shown on the map below. Reservations are of different sizes, and while it may appear as if many Tribes have quantified rights, only a small percentage of Tribes have a water rights settlement—fewer than one in 10.

- Some Tribes have also developed a water code to help regulate the use of water and activities that impact their water resources, which can be a useful tool for implementing a water rights settlement. Some Tribes have also enacted their own water quality laws and regulations as part of their water codes.

- A water code can outline the Tribe’s definition of water rights, priorities and procedures for granting and enforcing water use permits. It also helps ensure due process and fair procedures for users in water-related decision-making.

In summary, the creation of Tribal Reservations implied a right to adequate amounts of quality water. The quantification of water rights through settlements is one way to raise essential capital to build critical infrastructure and provides another legal basis to more fully access these rights. A water code can further define a Tribe’s vision for water management and outline procedures and regulations to enforce this management regardless of whether they have a negotiated settlement. Tribal sovereignty is a key consideration in any strategy to actualize a Tribal Nation’s right to water.

USEFUL LINKS

The United States Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs has information on recognized Tribes and Native Peoples, including a Tribal Leaders Directory showing leadership and location information. Their regulations on Tribal Water Codes are here and information on streamlining Tribal Water Codes is here.

The U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary's Indian Water Rights Office (SIWRO) manages, negotiates and oversees implementation of settlements of Tribal water rights claims. Their website includes a list of enacted water rights settlements.

The 377 ratified American Indian treaties within the U.S. National Archives can be found here.

The U.S. Library of Congress has information on the history of Tribal Water Rights Settlements on its website here.

The Inter Tribal Council of Arizona has information on the Winters Doctrine, including a link to the original U.S. Supreme Court Decision, on its website here.

The USDA 2022 Census of Agriculture has information on farm size and irrigated acreage on American Indian Reservations. More information is here.

FURTHER READING

Colby, B. and Young, R. 2018. Tribal water settlements: economic innovations for addressing water conflicts. Western Agricultural Economics Association, Vol. 16, Issue 1. Available here.

Kulikowski, M. 2023 Study: Tribal Water Rights Underutilized in U.S. West. News Release on the website of North Carolina State University. Available here.

Sanchez, L., Leonard, B., and Edwards, E.C. 2023. Paper Water, Wet Water, and the Recognition of Indigenous Property Rights. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, volume 10, number 6, November 2023. Available here.

Acknowledgements:

Comments and guidance from Brian Gray, Senior Fellow, PPIC Water Policy Center and Professor Emeritus, University of California College of Law, San Francisco.

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Office of the Chief Economist (OCE). The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

Footnotes

1 Tribe means federally recognized Tribe or Nation as listed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. A Reservation refers to an area of land designated as Federal Territory and governed by a Tribal Nation. Links to references and further reading are provided at the end of this publication.

2 Prior appropriation holds that the first person to use a particular water source has a right to use it before later users. This right can however be forfeit if the first user does not use the water. Under the law of all western states, appropriative rights can be reduced or lost if the appropriator fails to apply the water to a beneficial use over a specified period, uses water wastefully or unreasonable, or otherwise abandons or forfeits its rights. These state laws do not apply to federal reserved water rights, including tribal reserved rights.

3 The Tribal Reservation areas on this map were downloaded from the U.S. Census Bureau here. The Settlements are from the U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary's Indian Water Rights Office list found here.