Melkani, A., Rimšaitė, R., Brozović, N., Mieno, T.

Driven by concerns about long-term water availability in the face of extended and severe droughts, the regulation of agricultural groundwater use is attracting considerable attention in the American West. In states such as California there are debates and nascent conflict over the potential impacts on local agricultural economies of new water use restrictions. However, there has been little study of the economic impacts of existing agricultural groundwater use policies.

The state of Nebraska is heavily reliant on groundwater for supporting its agricultural economy. Over the last 50 years, a greatly varied set of groundwater management policies has emerged in Nebraska. This offers the opportunity to understand some of the economic impacts of groundwater regulations and to provide meaningful input to the larger groundwater management debate.

In some of our ongoing research, we are analyzing how two widespread agricultural groundwater regulations have affected farmland values. Changes in farmland values as a result of regulations are a direct and convenient indicator of the impact of regulations on rural economies. Economists think of farmland sales values as the capitalized value of expected profits that can be obtained on that farmland. So if we observe a reduction in farmland sales values, it suggests that there is an expectation of reduced future profits from that land. If replicated across a large area, this would suggest a shrinking of the local economy. While our research is still in progress, our results are interesting enough that we’re sharing them here for a general audience, rather than the technical audience of a peer-reviewed economics journal.

We focus on two types of regulations that have been adopted across Nebraska:

- Well moratoria – These are prohibitions on the development of new high-capacity wells in a specified area. Dryland covered by a moratorium cannot be developed for groundwater irrigation in the future.

- Groundwater allocations or quotas – These are upper limits on the volume of groundwater that can be pumped per acre of irrigated farmland over a specified period. In Nebraska, allocations are usually made over periods of three to five years. This allows some flexibility in the amount of water that can be extracted within a year: producers are allowed to and typically do extract more in dry years and less in wet years, so long as the total water extracted does not exceed the limit for the entire allocation period.

There are a couple of ways these regulations can potentially change farmland values. On one hand, they can reduce the current or future water use and thus decrease land productivity and value. On the other hand, these regulatory tools are designed to help prevent future depletion of water, suggesting they can potentially increase land productivity and value in the long term. These impacts are likely to differ across the two types of regulations and between irrigated and dryland farms.

For example, well moratoria are not likely to affect the water use of irrigated land. They can, however, impact dryland values by taking away the option to irrigate in the future. The impacts of water allocations are more challenging to hypothesize. It is straightforward to imagine that water allocations can reduce water use and, thus, land productivity. However, in practice, water allocations do not always result in water use reduction, as some farmers’ historical annual groundwater use is within the implemented allocation limits. There are multiple flexible tools designed to help ensure that farmers can reliably irrigate cropland while also meeting the allocation limits. Such tools include saving unused allocation water to have a higher limit in the next allocation period and managing allocations jointly across multiple fields. We use data to check which, if any, of these hypotheses hold water.

What we did

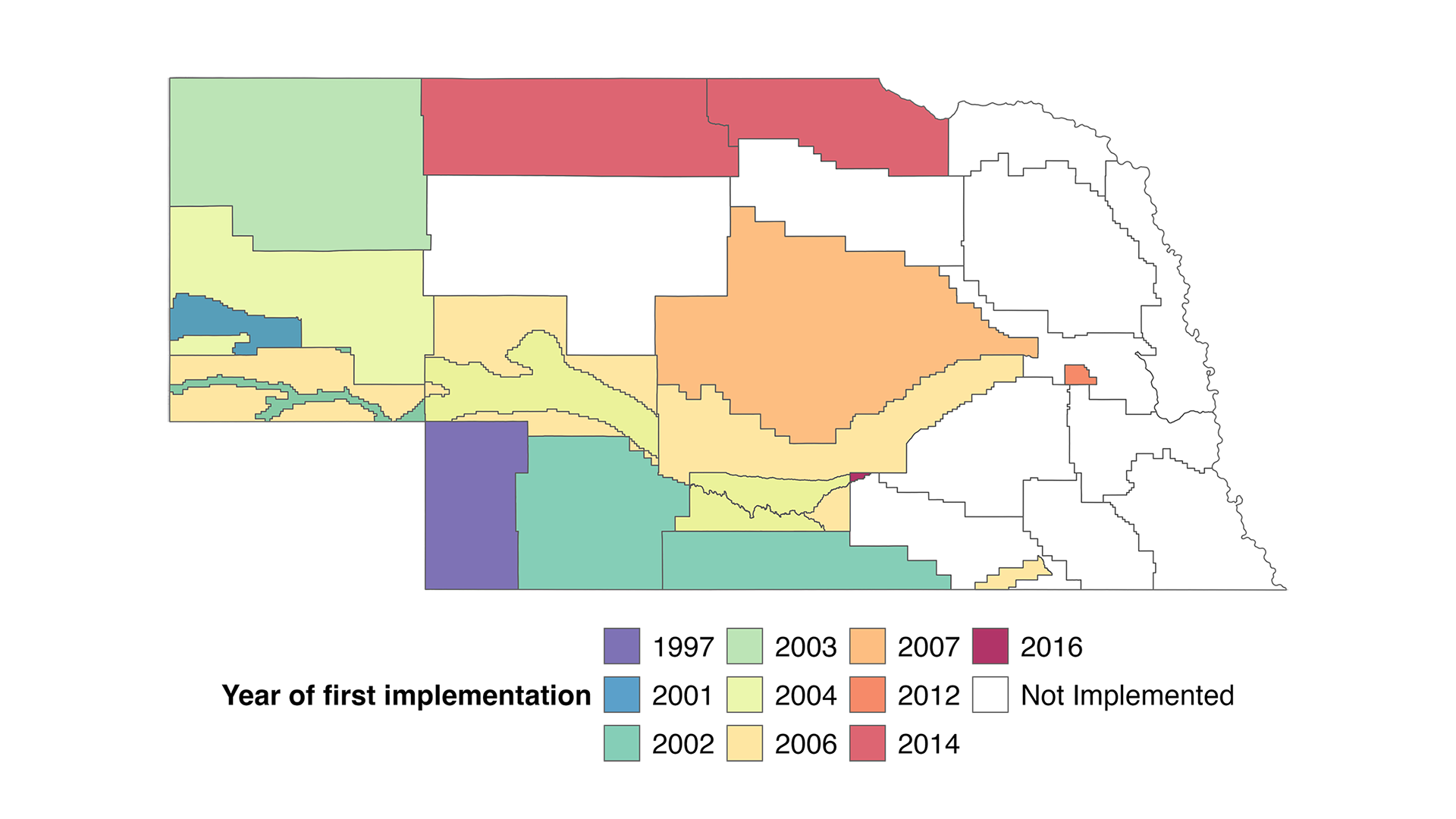

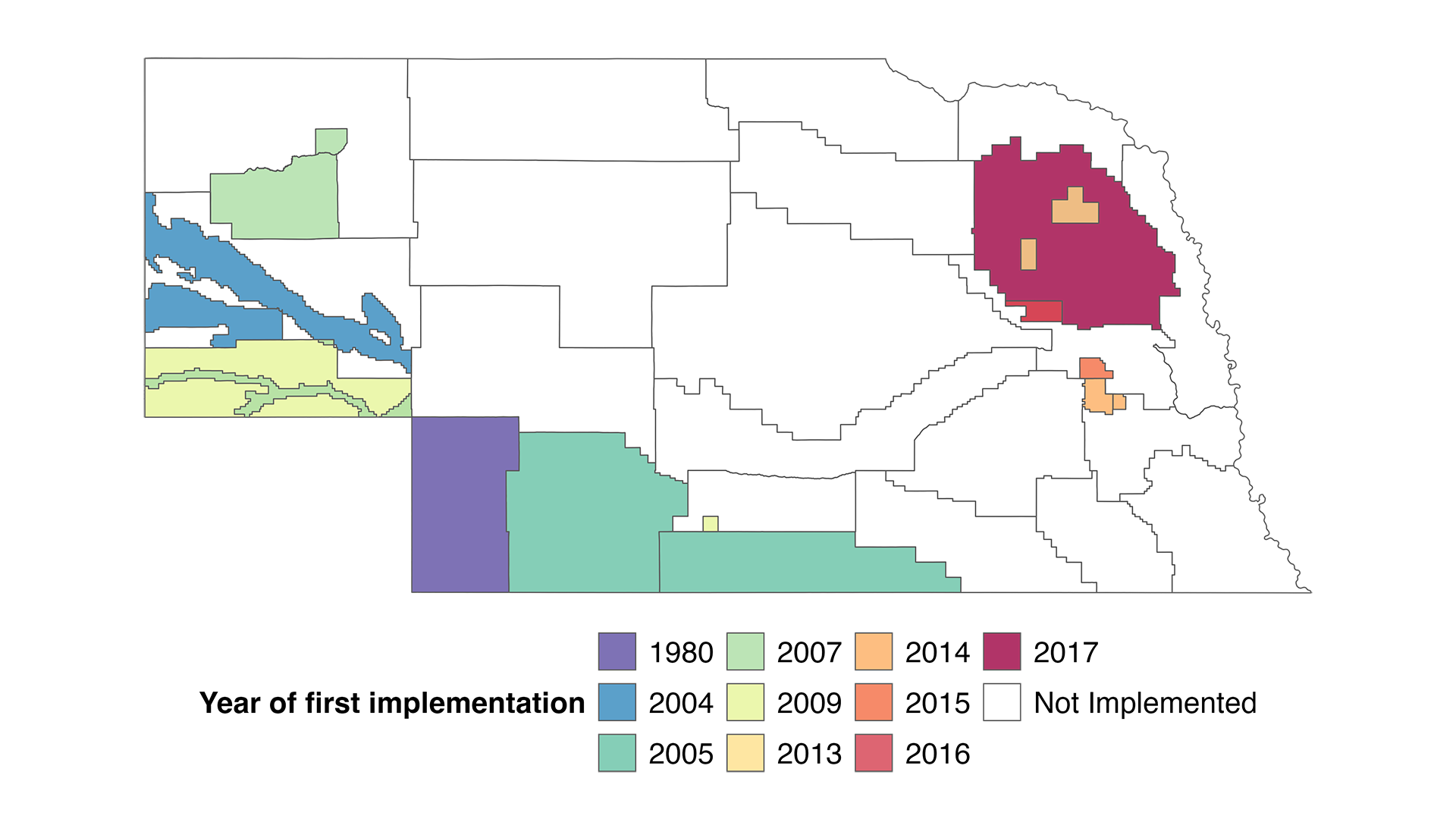

Groundwater regulations in Nebraska are implemented by 23 local governments known as the Natural Resources Districts (NRDs) whose responsibilities include ensuring long-term groundwater sustainability. We collected data on the evolution of groundwater regulations in Nebraska from various NRDs’ policy documents and through conversations with NRD leaders. These data are summarized in Figures 1 and 2. Both regulations were first implemented in the drier Southwestern region and have gradually spread to the North and East. It is worthwhile to note that the evolution of the regulations took place over decades and that their landscape continues to evolve as new challenges in water access emerge.1

Figure 1: Evolution of groundwater well moratoria in Nebraska

Spatial and temporal data about the implementation of groundwater well moratoria and allocations across NRDs were then matched with data on farmland sale values, groundwater rights (to indicate the irrigated or dryland status of the land), weather, soil, and other characteristics between 2005 and 2021. (The choice of years was restricted by the availability of data on farmland sale values.) We analyzed this information to check how land values change in areas where groundwater regulation is “switched on” versus those where they remain “switched off.”i

What we found

1. Following a well moratorium, the value of dryland parcels fell by 9%. This is equivalent to an average loss of $200/acre at inflation-adjusted prices. As mentioned above, this is likely because dryland parcels facing well-moratoria lose the potential for developing the land for more productive irrigated agriculture in the future.

Policy takeaway: Policymakers may want to be cautious of the unanticipated detrimental impact of regulations akin to well moratoria for farmers without secure water rights. These include any policies that preclude the expansion of irrigation to new areas/users.

2. Land values remained unperturbed by the imposition of groundwater allocations. The anticipated effect of the groundwater allocations was not straightforward. It could be that the inherent flexibility of this regulation allows farmers to continue irrigating their crops without facing significant losses in crop productivity while also meeting regulatory norms. Also, in practice, groundwater allocations are not always binding. As a result, the implementation of this regulation may not lead to significant water use reduction for all affected farmers, and thus may not affect their farmland prices either.

Policy takeaway: Policymakers may find groundwater allocations to be a fairer alternative to well moratoria or similar policies focusing on limiting the possibility of future irrigation expansion.

3. Neither regulation – well moratoria or groundwater allocations – had any significant effect on the values of land that had already been developed for irrigation prior to the implementation of the regulation. It is likely that these parcels have already capitalized the value of the groundwater resources into their market value and future regulations do not threaten this capitalized value.

Policy takeaway: This evidence may help alleviate some of the irrigating farmers’ concerns related to the potential impacts of new groundwater regulations, at least, in the case of the regulations discussed in this blog.

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Office of the Chief Economist (OCE). The findings and conclusions in this blog are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

References

i Melkani, A., Mieno, T., Hrozencik, R. A., Rimšaitė, R., Brozović, N., & Kakimoto, S. (2023). Economic Impact of Groundwater Regulation in Nebraska: A Hedonic Price Analysis.

1 The information in this blog is up-to-date as of September 2023. We considered regulations that have been implemented by a change in local law and is irreversible without an amendment in that law. Many NRDs have relied on temporary regulations at various points of time. However, these temporary regulations were not the focus of our study.