In science, “colors” of water are classified based on where they can be found in nature. Green water is the moisture stored in soil as a result of precipitation and is used by plants through transpiration. It is the main source of water to produce items for human use, including food, feed, fiber, timber and bioenergy. Blue water is groundwater (like aquifers) or surface water, including that stored in lakes, streams, snow, or glaciers. Research typically focuses on scarcity of blue water because its effects are more easily seen, but a new study considers limits to the green water flow allocated to human society. DWFI Postdoctoral Research Associate Mesfin Mekonnen and colleagues say that by ignoring these limits, we could risk further loss to parts of our ecosystem that rely on untouched green water flows.

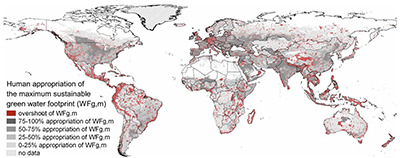

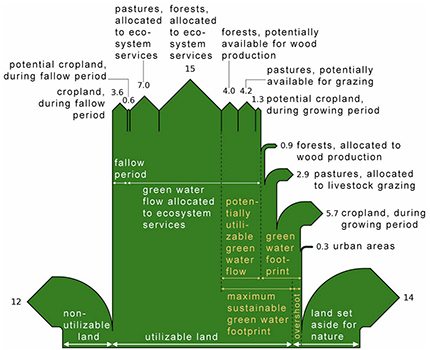

About 22 percent of global green water flow is from undeveloped natural lands land set aside for nature, while 17 percent is from unusable lands due to temperature, steep terrain, or distance from human activity. The rest of the green water flow (62 percent) is partly allocated to human activities and part to habitat, climate regulation, erosion control and other necessary ecosystem services. Researchers in the study found that on a global level, 56% percent of the world’s sustainably available green water flow is already allocated to human activities, but that amount varies greatly by region. They suggest increasing green water productivity through a vapor shift – increasing the soil’s water-holding capacity through solutions like no-till and reduced tillage systems to conserve soil organic matter. This turns non-beneficial evaporation into transpiration that contributes to biomass growth.

The researchers also note that the result of green water scarcity is not as visible as that of blue water. Blue water scarcity can be seen in reduced rivers flows and declining levels in groundwater, rivers and lakes and is more immediately recognized by people depending on the water availability. On the other hand, green water scarcity is the result of land-use decisions. When green water is scarce, the green water that was once available to natural vegetation is now being used to produce outputs for the human economy. Exploring both green and blue water resources together can better inform assessments and discussions of water scarcity, food security, or bioenergy potential.